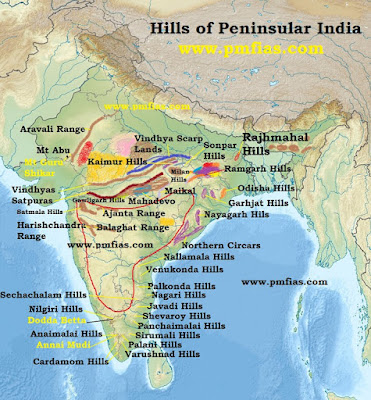

Central India has a mountain range that runs east to west known as the Vindhya.

Despite their diminutive stature, they have long served as a cultural barrier between northern and southern India.

As per mythological scriptures the Vindhya were long seen as an uncivilized and potentially dangerous place, inhabited by ghosts, demons, and tribal peoples; these dangers were exemplified by Vindhyavasini, the presiding goddess.

The Vindhya Mountains and Agastya Muni

Agastya Muni's stories may be found in the Vedas, Puranas, and Itihaasa.

Both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata tell the story of this episode.

When they visit the tirtha where Agastya Muni once murdered Vatapi in the Mahabharata, Lomasha Rishi informs Yudhishthira about numerous tales from Agastya Muni's life.

Mount Meru used to be circumambulated by the sun.

'O Bhaskara!' protested Vindhya, a rival mountain, to Suryadeva.

Meru is something you constantly go around.

'In the same manner, circumambulate me.' 'O mountain!' Suryadeva answered to Vindhya, the ruler of the mountains.

I don't do it because I want to.

This is the road that the creator of the universe has chosen for me.'

Vindhya was enraged, and he started to grow taller all of a sudden.

He desired to prevent the sun, moon, and stars from orbiting Meru.

Vindhya grew and grew and grew.

The devas were terrified.

All the devas gathered with Indra sought to persuade Vindhya to cease growing, but he refused.

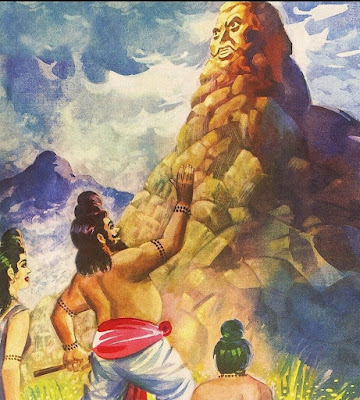

Finally, the devas came to Agastya Muni's hermitage and told him about their dilemma.

They begged him to intercede, claiming that he was the only one who could stop Vindhya.

Agastya Muni and Lopamudra, his wife, set off for Vindhya.

'O greatest among mountains!' said the rishi to the mighty mountain.

I'd want for you to pave a way for me.

For some reason, I need to go to the south.

Indra, king of the mountains! 'Restrain yourself until I return from there, and then you may grow as much as you want.' — p.

86 (399(102)) of Bibek Debroy's English translation of the Mahabharata.

Vindhya consented and shrank in size to allow Agastya Muni to pass through.

While the writings do not go into depth, one may envision the king of the mountains' admiration for Agastya Muni for agreeing to his request while rejecting all of the devas' requests combined.

It is stated that Agastya Muni and his wife left in the direction of the south and never returned.

The Vindhya mountains are still present, but at a lower elevation.

This might be viewed as a simple narrative, a fable attempting to explain a geographical phenomena.

Or, as a fable about the pitfalls of ego, Vindhya has been duped into waiting for the rishi who will never come, unable to reclaim its beautiful heights for all eternity.

A more inspiring and constructive view is that when a person possesses shraddha, or respect, for a knowledgeable entity, he or she will be rescued.

The Vindhya Mountain lives today because to Agastya Muni's protection; if the king of mountains had persisted in his refusal, it would have been destroyed.

He was rescued because the monarch of the mountains showed homage to the great rishi.

There's also one more subtle, interesting component to the story.

In the south, Agastya Muni says he has 'job to do.' He doesn't say what kind of job it is.

However, a rishi's word, especially that of a renowned rishi like Agastya Muni, who is considered one of the saptarishi in certain ways, should never be taken lightly or discarded.

It always contains satyam, or truth.

Is the true narrative about the humbling of a mountain, or about the trek of a rishi with 'job to do' beyond the Vindhya mountains' range?

Why did the devas chose Agastya Muni in particular for this task?

Why did Vindhya choose to rebel at this particular moment?

Were they the circumstances that allowed something else, something more significant, to happen?

Was this simply the beginning of a larger effort to promote the Dharma?

This story may have served as a pretext for Agastya Muni to introduce his Dharma teachings to the southern areas, much as Padmasambhava journeyed from India to Tibet to establish Buddhism in Tibet and Bodhidharma brought Buddhism to China.

A Fascinating Dialogue Begins When Jaimini Rishi Meets The Four Birds Now, let's return to our main narrative.

Jaimini Rishi visits the Vindhya Mountain and enters a tunnel where the four birds are residing.

The stone floor of this hallowed hole is wetted by drips from the Narmada River.

When the rishi sees the four birds, he thinks to himself, 'This is a lovely area.' They have maintained control of their respiration without taking any interruptions.

These magnificent birds are reciting clearly and flawlessly.

These sage's sons have now given birth to a new species, and I believe it's fantastic that Sarasvati hasn't abandoned them.

A person's vast number of relatives and friends, as well as everyone else who is treasured at home, might forsake and leave them.

But Sarasvati remains.' — Bibek Debroy's English translation of Markandeya Purana, p. 19

In their position as Panchama Veda, the Itihaasa and Puranas are tasked with instilling vairagya (compassion) and viveka (discrimination between nitya (that which is everlasting, or more accurately, beyond the purview of Time) and anitya (that which is not).

It does this not just via logical ratiocination, but also through the power of rasa, the development of a field of immersive experience and emotion that we go through when reading or listening to a narrative.

It is stated that there are three ways to learn that fire burns: being informed that it burns, seeing someone else being burnt, or being burned yourself.

The uttama adhikara (the most qualified one) is told once and does not need to be told again; the ones of middling adhikara (which most of us can at least aspire to achieve in this lifetime or the next) can learn from others, including through stories; the unfortunate ones (which would be most of us if we do not engage in sadhana and improve ourselves) will have to learn through suffering again and again.

That is why the Puranas are so important: we may learn knowledge from them without having to go through the same unpleasant experience ourselves.

When we reflect on the pitiful story of these four birds, who were asked by their father to give up their lives and then cursed by him, who were born on the battlefield and spent the first part of their lives hidden in the darkness of a bell that hung around the neck of a slain elephant, we find that only Sarasvati Devi, only that shining light of vidya through sadhana and study of the shastras, remains with us in the end.

The birds are introduced to Jaimini Rishi.

Padya (offering of water to wash his feet) and arghya (offering of food) are two ways they respect him (offering of water to wash his hands).

They cool him by fanning him with their wings.

'We have led excellent lives and our births have been successful today,' Jaimini Rishi says, as the birds welcome her.

We hope that your hermitage's animals, birds, trees, creepers, bushes, bark groves, and grass are all doing well.

Perhaps by asking this question, we have showed you disrespect.

'How could those who are with you not be in good health?' — Markandeya Purana English translation by Bibek Debroy, p.

20 This is the amount of sattva and compassion that our culture embodied.

When kings and rishis met, or when kings met, they inquired about the well-being of the people in their kingdoms, the status of the treasury, and if the dharma was being kept.

Even grass blades are being investigated – no living form is left out.

The sensation of oneness with all existence is referred to as sarvatma bhava.

The purpose of Jaimini Rishi's visit, he says, is to alleviate his misgivings about the Mahabharata.

'If it's a topic we're familiar with, we'll make you hear it without hesitation,' the birds say.

Why won't we tell you what is within our intelligence's scope?

O lord of the brahmanas! Our intellect can comprehend the four Vedas, the Dharmashastras, all the Angas, and anything else that is in accordance with the Vedas.

Despite this, we can't make any guarantees.

So, without hesitating, tell us about your concerns concerning the Bharata.

Who knows about dharma?

Otherwise, there would be a lot of misunderstanding.' ― p. 21 of Bibek Debroy's Markandeya Purana English version Again, notice the humility that lies behind the knowledge.

Even while the birds concede that they understand all of the shastras, or Vedic wisdom, they cannot absolutely guarantee that they would be able to answer his questions.

They also hold him in high regard as a dharma expert.

The first question is how the formless one (Narayana) could take on a human form (Sri Krishna).

The birds begin by prostrating before Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva.

They go on to say that Vishnu is both nirguna (without characteristics) and saguna (with attributes), and that he exists in four different forms: The first kind is undetectable.

It seems white to those who have studied it.

Yogis envision someone whose limbs are encircled in flame garlands in this shape.

It is distant; it is close; it is beyond the gunas, the shape and colour conjured up by the mind.

Vasudeva is my name.

Shesha, the serpentine one who supports the ground, is the second form.

Tamas are a feature of this type.

Sattva is embodied in the third form.

This is the form that creates and maintains dharma, as well as caring and safeguarding mortals.

Vishnu slays asuras and rakshasas in this form before descending into his avatara forms.

Pradyumna is his name when he descends as the guardian in a form of pure sattva.

Narayana, lying in the sea on Shesha's back, is the fourth form.

This shape is continually in the phase of production, steeped in rajas.

You may also want to read more about Hinduism here.

Be sure to check out my writings on religion here.