Chera Dynasty is a historical dynasty in India.

From the second century B.C.E. until the ninth century C.E., a Hindu dynasty controlled most of what is now Kerala.

The Cheras were always at odds with the Pandyas and Cholas, the two major kingdoms in the deep south, and were ultimately annexed by the Cholas in the ninth century C.E.

Who is the Chera dynasty's founder?

Cheral Athan Uthiyan From Tamil literature, Uthiyan Cheral Athan is widely regarded as the first known king of the Chera line (and the possible hero of the lost first decade of Pathitrupattu).

"Vanavaramban" was another name for Uthiyan Cheral (Purananuru). His base of operations was at Kuzhumur (Akananuru).

Chera Script

|

Inscription of Irumporai Cheras from Pugalur Velayudhampalayam, Arunattarmalai Irumporai, Perum Kadungon [Irumporai], Ko Athan Chel (Cheral) [Irumporai], Ilam Kadungo |

Early Cheras epigraphic and numismatic evidence has been discovered through archaeology.

What is the location of the Chera dynasty?

Cera dynasty, sometimes spelt Chera, rulers of a historic kingdom in what is now Kerala state in southern India, also known as Keralaputra.

Cera was one of the three main kingdoms of southern India that made up Tamilkam (Territory of the Tamils), with its capital on the Malabar Coast and its hinterland.

Who is the most powerful king of the Chera dynasty?

Sengutturan.

According to Chera legend, Sengutturan was the greatest monarch of the Chera dynasty.

The Chola and Pandya rulers had been vanquished by him.

At the close of the third century A.D., the Chera's authority began to wane. In the eighth century A.D., they regained power.

What Was The Chera Coinage?

A handful of coins thought to be Cheras, mainly discovered in Tamil Nadu's Amaravati riverbed, are a significant source of early Chera history.

A number of punch-marked coins were found in the Amaravati riverbed. Copper and its alloys, as well as silver square coins, have been found.

On the obverse, most of these early square coins had a bow and arrow, the Cheras' traditional symbol, with or without a legend.

There have been reports of silver-punch stamped coins with a Chera bow on the reverse, which are a replica of the Maurya coins.

Hundreds of Chera copper coins have been found in Pattanam, Kerala's central district.

In a riverbank in Karur, bronze dies for minting punch marked coins were found.

A coin with a portrait and the Brahmi inscription "Mak-kotai" above it, as well as another with a picture and the legend "Kuttuvan Kotai" above it, were also discovered.

Both impure silver pieces are thought to be from the first century CE or later. Both coins have a blank back side.

Karur also produced impure silver coins with Brahmi legends "Kollippurai", "Kollipporai", "Kol-Irumporai" and "Sa Irumporai".

In general, portrait coins are thought to be imitations of Roman coinage.

On the reverse, all legends were written in Tamil-Brahmi characters, which were believed to represent the names of Chera kings.

The bow and arrow emblem was often seen on the reverse.

A joint coin with the Chola tiger on the obverse and the Chera bow and arrow on the reverse demonstrates the Cholas' partnership.

Karur has also yielded Lakshmi-type coins with a probable Sri Lankan provenance.

The macro study of the Mak-kotai coin reveals striking resemblances to modern Roman silver coins.

In Karur's Amaravati riverbed, a silver coin with a picture of a person wearing a Roman-style bristled-crown helmet was also found.

The Chera family's traditional emblem is a bow and arrow, which is shown on the reverse side of the coin.

Who is the final Chera dynasty king?

Kulasekhara Rama Rama Kulasekhara (late 11th century CE) was the final king of medieval Kerala's Chera Perumal dynasty.

Chera rulers belong to what Hindu Caste?

The Villavars of Chera Kingdom, were the Illavas or Ezhavas with roots in Sri Lanka, and this clan also branched out to the Karnataka Billavas.

The Rajput Kshatriya clans of Bhil Meenas of Rajasthan, Meenas of Rajastan, and Bhils of North India belong to the same Kshatriya Warrior Caste lineage.

What Constituted The Chera Economy?

Trade in spices.

|

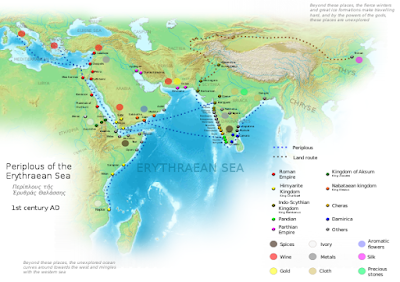

Spice Routes (Blue) and Silk Road (Red) |

The Chera chiefdom's trade connections with the Graeco-Roman world's merchants, the "Yavanas," and with north India supplied significant economic impetus.

The main economic activity was trade over the Indian Ocean.

When it comes to the nature of the "spice trade" in ancient Chera land, there is considerable disagreement.

Given the presence of seemingly uneven governmental structures in south India, it is debatable if the Tamil merchants conducted this "trade" with the Mediterranean world on equal terms.

Because it occurred between the Roman Empire and South India with unequal chiefdoms, some more recent scholars claim that the "trade" was a "severe imbalance" transaction.

The Cheras became a major power in ancient southern India due to geographical advantages such as favorable Monsoon winds that carried ships directly from Arabia to south India, as well as an abundance of exotic spices in the interior Ghat mountains (and the presence of a large number of rivers connecting the Ghats to the Arabian Sea).

Spice trade between Middle Eastern and Mediterranean (Graeco-Roman) navigators dates from before the Common Era and was mostly cemented throughout the Common Era's early years.

The Romans conquered Egypt in the first century CE, which helped them gain supremacy in the Indian Ocean spice trade.

Pliny the Elder in the first century CE, Periplus Maris Erythraei in the first century CE, and Claudius Ptolemy in the second century CE are the first Graeco-Roman descriptions of the Cheras.

The Periplus Maris Erythraei depicts the "commerce" in Keprobotras' area in great detail.

Muziris was the most significant city on the Malabar Coast, which "abounded with great ships of Romans, Arabs, and Greeks," according to the Periplus.

Spices in bulk, ivory, wood, pearls, and jewels were "exported" from Chera to Middle Eastern and Mediterranean countries.

The Romans are reported to have brought large quantities of gold in exchange for black pepper.

The discovery of Roman coin hoards in different areas of Kerala and Tamil Nadu attests to this.

Pliny the Elder laments the loss of Roman money to India and China in exchange for luxuries such as spices, silk, and muslin in the first century CE.

The fall of the Roman empire in the 3rd and 4th century CE slowed the spice trade across the Indian Ocean.

With the Mediterranean's departure from the spice trade, Chinese and Arab navigators stepped in to fill the void.

Trade In Wootz Steel

The wootz crucible steel from medieval south India and Sri Lanka was used to create the renowned damascus blades.

High carbon Indian steel is mentioned in ancient Tamil, Greek, Chinese, and Roman literature.

The crucible steel production process began in the 6th century BC at the production sites of Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu, Golconda in Telangana, Karnataka, and Sri Lanka, and was exported globally; by 500 BC, the Chera Dynasty had produced what was referred to as the finest steel in the world, i.e.

Seric Iron, which was sold to the Romans, Egyptians, Chinese, and Arabs.

Steel was shipped in the form of steely iron cakes known as "Wootz."

Wootz steel from India has a high carbon content.

To fully remove slag, black magnetite ore was heated in the presence of carbon in a sealed clay crucible within a charcoal furnace.

Smelting the ore first to make wrought iron, then heating and hammering it to remove the slag was another option.

Bamboo and leaves from plants like Avrai provided the carbon supply.

By the 5th century BC, the Chinese and natives in Sri Lanka had acquired the Cheras' wootz steel manufacturing techniques.

This early steel-making technique in Sri Lanka used a unique wind furnace powered by monsoon winds.

Antiquity-era production sites, as well as imported relics of old iron and steel from Kodumanal, have been discovered in locations like Anuradhapura, Tissamaharama, and Samanalawewa.

Some of the first iron and steel artifacts and manufacturing techniques from the classical era were introduced to Sri Lanka by a 200 BC Tamil trading guild at Tissamaharama, in the south east.

You may also want to read more about Hinduism here.

Be sure to check out my writings on religion here.

References And Further Reading

Coomáraswámy, P., 1895. II.—King Sen̥kuțțuvan of the Chera Dynasty. The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 14(46), pp.29-37.

DYNASTY, C., 2015. CHENLA EMPIRE (500s–800s CE). World Monarchies and Dynasties, p.173.

Majumdar, S.B., 2016. Chera Kingdom. The Encyclopedia of Empire, pp.1-3.

Raja, S., Role of Information Technology in Teaching and Learning of Classical Literature.

Uskokov, A., 2014. Mukundamālā of Kulaśekhara Āḻvār: A Translation: Journal of Vaishnava Studies. Journal of Vaishnava Studies, 22(2), pp.207-224.

Lakshmi, S., A Study on “Kerala Style” Temple Architecture and Its Uniqueness.

Nair, K.R., 1997. Medieval Malayalam Literature. Medieval Indian Literature: An Anthology Volume One, pp.299-323.

Nair, A., From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Nair dynasty).

Malabar, N.T.K.T.S. and Kasaragod, W.N.M., The word Malayalam originated from the words mala, meaning" mountain", and alam, meaning" region" or"-ship"(as in" township"); Malayalam thus translates directly as" the mountain region." The term originally referred to the land of the Chera dynasty, and only later became the name of its language.[17] The language Malayalam is alternatively called Alealum, Malayalani, Malayali, Malean, Maliyad, and Mallealle.[18].

NAYAR, V.S., 1993, January. PEARLS CAST BY THE SWINES: A STUDY OF MALAMAKHALI AS A SOURCE MATERIAL FOR CULTURAL HISTORY (SUMMARY). In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress (pp. 924-925). Indian History Congress.

NAYAR, V.S., 1993, January. PEARLS CAST BY THE SWINES: A STUDY OF MALAMAKHALI AS A SOURCE MATERIAL FOR CULTURAL HISTORY (SUMMARY). In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress (pp. 924-925). Indian History Congress.

Tower, T., Celina, B., Epoque, B. and Kashyap, A.O., 2018. Kerala State. Population, p.2.

Thoma, P.J., 1923. The identification of Satyaputra. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 55(3), pp.411-414.

Abraham, A.M., Where The Flavours of The World Meet: Malabar As A Culinary Hotspot.

Lemercinier, G., 1979. Kinship relationships and religious symbolism among the clans of Kerala during the Sangan period (first century AC). Social compass, 26(4), pp.461-489.

Sasisekaran, B. and Rao, B.R., 2003. (02) Archaeo Metallurgical Study on Select Pallava Coins.

Kumar, N.R. and Rajkumar, N.V., 1940. EVOLUTION AND WORKING OF THE GOVERNMENT IN TRAVANCORE. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 2(2), pp.217-240.

DYNASTY, P., 2005. Arikesar Maravarman was a great soldier who. World Monarchies and Dynasties, 1, p.716.

Cherian, S.B., Journal Homepage:-www. journalijar. com.