Asura Marriage is one of the eight methods to conduct a marriage that the Dharma Shastras, or religious treatises, acknowledge (dharma).

- It is called after the asuras, a strong celestial demoniac race whose goals often conflict with those of the gods (deva), giving the term a negative meaning.

- When a man provides money to the bride's family and the bride herself, it is called an asura marriage. (Buying a Bride).

- As is observed in most modern societies globally, an asura marriage is characterized by its transactional nature where in sacred marital vows are not consented to or volunteered by devotion or affinity, but rather sold in exchange for financial gain, be it capital, immovable or in kind.

- In an age of increasing divorces and infidelity, this unholy form of marriage has taken center stage among global societies in the Kali Yuga.

Because of the implication that the bride is being sold, this is one of the four terrible (aprashasta) types of marriage; nevertheless, like the other deplorable forms, it is considered to establish a legal marriage.

- Despite this widespread condemnation, it is one of the two traditional types of marriage that is still performed (the other being Brahma marriage).

- Because of the shame associated with the connotation of selling one's child, it is only done by the impoverished or those of low social standing.

Definition Of Asura marriage according to Manu Smriti's section IV - Eight varieties of marriage.

It is known as Asura marriage when a man (groom) brings away a lady (bride or maiden) after offering riches as may be desired by her father on the plea to reclaim the money spent on her upbringing.

- This is recommended for Vaishyas and Shudras among four varnas of the Hindu social order in Hinduism, as specifically mentioned in Manu Smriti (Verse 3.21) among eight types of marriages defined in Hinduism, namely

(1) Brahma,

(2) Daiva,

(3) Arsha,

(4) Prajapatya,

(5) Asura,

(6) Paishacha

This kind of marriage is not encouraged for Brahmins and Kshatriyas, and it is hence illegal.

- Typically, it is determined by the man's will and desire, as well as his riches, regardless of the bride's willingness.

- This sort of marriage entails paying a fee to the bride's relatives in order to purchase her. Or the Asura kind of marriage requires the bridegroom to provide money directly to the bride's father or kinsman.

- A wealthy but incompetent guy may have as many wives as he wants by taking advantage of this sort of marriage, whereas a poor but competent man may not be able to pay the money to be paid.

Why is Asura marriage seen as inferior rather than dignified?

- The bridegroom determines the fee based on the bride's family's social standing.

- Money is the most important factor in this kind of marriage.

- In this kind of marriage, the bride is essentially bought.

- The groom in an Asura marriage is not at all fit for the bride. He happily provides the bride's parents and relatives as much money as he can. It may be seen as a bribe in exchange for the boy's desire for the girl, even if he is in no way a match for her.

- As a result, the marriage system is similar to purchasing a commodity, which makes it unpopular in today's society. The groom is usually from a lower social class or caste than the bride.

The Asura marriage is either an ancient habit or a necessary evil, according to the Smriti authors.

According to Manu, the girl's smart father should not take even the smallest sum of money.

- If he accepts it, he will be referred to as a child seller.

- This kind of marriage is still widespread among low-caste Hindus and several other Indian tribes today.

- Because of the dowry system and other factors, it is not praised by knowledgeable people.

Unapproved forms of Hindu Marriage.

The unapproved forms of marriage include Asura, Gandharva, Rakshasa, and Paisacha.

- The property of a childless woman married in one of the prohibited forms falls to her family rather than her spouse, according to Rajbir Singh Dalal versus Chaudhari Devi Lal University, 2008.

Asura Marriage In Mythology.

- This is one of the most often denounced types of union. The father of the bride gives away her daughter in this fashion after the bridegroom has offered all of the riches he can to the bride's father and the bride herself.

- The guardian of Kaikeyi was granted an exorbitant sum of money for her marriage to King Dasaratha, according to the Ramayana.

- This was essentially a business transaction in which the bride is bought.

Modern Day Asura Marriage In India.

In the case of Kailasanatha Mudaliar v. Parasakthi Vadivanni, 1931, the standard for deciding whether a marriage is "asura" or not was established.

- Asura marriage occurs when the bridegroom provides money or anything of value (such as wheat, cows, or other livestock) to the bride's father for his profit or in exchange for him giving her daughter in marriage.

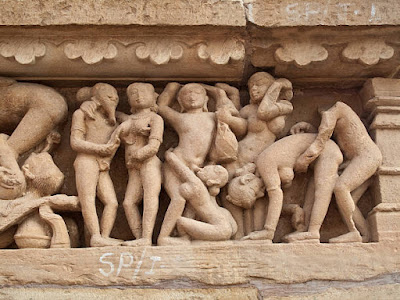

Rakshasa Marriage.

The bride is kidnapped and her family and relations are ruthlessly murdered in the Rakshasa style of marriage.

- Another need, according to certain writings, is that the bridegroom battle with the bride's family while following the ceremonial rituals in a peaceful wedding.

- This criterion, however, is not required for a "Rakshasa" marriage. According to renowned Indologist P. V. Kane, this kind of marriage is called Rakshasa because Rakshasas (demons) are believed to have been brutal to their captives throughout history.

- Kshtraiyas, or military classes, practiced this kind of marriage. The "Rakshasa" marriage mimics a victor's claim over a prisoner of war.

This is a criminal offense under section 366 of the Indian Penal Code in the contemporary age. Abducting/kidnapping a woman to force her into marriage is punished by up to ten years in jail and/or a fine under Section 366.

Paishacha Marriage.

This is the eighth and last kind of marriage since it is the most heinous of the eight.

- A guy seduces a woman and performs a sexual act on her when she is asleep, inebriated, or mentally ill, usually at night.

- Because of the disgrace of such behavior, the girl and her parents must accept to the man's marriage.

- Paishacha refers to nighttime goblins who are intended to operate in secrecy.

It mimics rape, which is the most heinous conduct a person can do in the contemporary period and is punished under section 376 of the Indian Penal Code. Rape is punishable by a minimum of seven years in jail and a maximum of life in prison, as well as a fine.

Relatable Modern Marriages Observed in Today's World.

There are now only two types of marriage:

- Brahma and Asura, as mentioned in A. L. V. R. S. T. Veerappa Chettiar versus S. Michael Etc, 1962.

- The idea of a gift: The genesis of the dowry system in India has been attributed to Brahma marriages.

As stated in A. L. V. R. S. T. Veerappa Chettiar vs S. Michael Etc., 1962, the Asura marriage has developed from an actual sale transaction to a kind of marriage in which the parties' or community's knowledge implies that the marriage is "Asura" in origin.

- Other kinds have nearly gone obsolete in recent years, since they are now considered a criminal offense under the IPC and are considered inappropriate by society norms and morality.

- However, certain lower castes continue to perform and engage in these marital practices and behaviors, thus they are not completely gone.

Final Thoughts.

- The eight types of marriage, as outlined in dharma books such as the Manu-smriti, were developed to accommodate various classes of people.

- Brahmins were the ones who generally practiced the sanctioned marriage forms.

Some of these practices have been acknowledged as customary under the Hindu Marriage Act of 1956, while others have been made illegal under India's numerous penal codes.

Related to - The eight classical types of marriage.

You may also want to read more about Hinduism here.

Be sure to check out my writings on religion here.

References And Further Reading.

- Derrett, J. Duncan M. “AN ASPECT OF THE ARRANGED MARRIAGE IN DHARMAŚĀSTRA.” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 58/59 (1977): 107–20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41691682.

- Sternbach, L. and Dave, J.H., 1981. Manu-smriti with Nine Commentaries by Medhātithi, Sarvarjñanārāyaṇa, Kullūka, Rāghavānanda, Nandana, Rāmacandra, Maṇirāma, Govindarāja and BhāruciManu-smriti with Nine Commentaries by Medhatithi, Sarvarjnanarayana, Kulluka, Raghavananda, Nandana, Ramacandra, Manirama, Govindaraja and Bharuci. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 101(2). https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/manusmriti-with-the-commentary-of-medhatithi/d/doc199802.html

- GUPTA, GIRI RAJ. “Love, Arranged Marriage, and the Indian Social Structure.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 7, no. 1 (1976): 75–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41600938.

- Kumar, Vijender. “BIGAMY AND HINDU MARRIAGE: A SOCIO-LEGAL STUDY.” Journal of the Indian Law Institute 59, no. 4 (2017): 356–82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26826614.

- Schlegel, Alice, and Rohn Eloul. “Marriage Transactions: Labor, Property, Status.” American Anthropologist 90, no. 2 (1988): 291–309. http://www.jstor.org/stable/677953.

- Jayasekera, M. L. S. “MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE IN ANCIENT SINHALA CUSTOMARY LAW.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Sri Lanka Branch 26 (1982): 77–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23730735.

- Sternbach, Ludwik. “A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE FORMS OF MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT INDIA (A Résumé).” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 22, no. 3/4 (1941): 202–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43975949.

- Bhat, S.G. “LAWS OF MARRIAGE FROM ‘SASTRAS’ TO STATUTES - INEQUALITY TO EQUALITY.” Journal of the Indian Law Institute 45, no. 3/4 (2003): 400–408. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43951870.

- Chowdhry, Prem. “Private Lives, State Intervention: Cases of Runaway Marriage in Rural North India.” Modern Asian Studies 38, no. 1 (2004): 55–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3876497.

- Ranjana Sheel. “Institutionalisation and Expansion of Dowry System in Colonial North India.” Economic and Political Weekly 32, no. 28 (1997): 1709–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4405621.

- Bhattacharji, Sukumari. “Economic Rights of Ancient Indian Women.” Economic and Political Weekly 26, no. 9/10 (1991): 507–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4397402.

- Polit, Karin. “Gifts of Love and Friendship: On Changing Marriage Traditions, the Meaning of Gifts, and the Value of Women in the Garhwal Himalayas.” International Journal of Hindu Studies 22, no. 2 (2018): 285–307. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44983948.